Introduction to Command Line Interface

Outline:

- What is the command line?

- Directory Structure

- Syntax of a Command

- Logging Into a Remove Server

- Command Line Basics (ls, pwd, Ctrl-C, man, alias, ls -lthra)

- Getting Around (cd)

- Absolute and Relative Paths

- Tab Completion

- Create and Destroy (echo, cat, rm, rmdir)

- Piping and Redirection (|, >, », cut, sort, grep)

- History Repeats Itself (history, head, tail,

) - Editing Yourself (Ctrl-A, Ctrl-E, Ctrl-K, Ctrl-W)

- Compressions and Archives (tar, gzip, gunzip)

- Forced Removal (rm -R)

- BASH Wildcard Characters (?, *, find, environment variables($), quotes/ticks)

- Manipulation of a FASTA file (cp, mv, wc -l/-c)

- Symbolic Links (ln -s)

- STDOUT and STDERR (>1, >2)

- Paste Command (paste, for loops)

- Running in the Background (bg, &, nohup, jobs, kill, top)

- Shell Scripts and File Permissions (chmod, nano, ./)

A CLI cheat sheet

What is the command line

- CLI is a tool into which one can type commands to perform tasks.

- The user interface that accepts the typed responses and displays the data on the screen is called a shell: bash, tcsh…

- An all-text display (most of the time your mouse doesn’t work)

A greater than sign (>) instead of a prompt means the shell is expecting more input. Can Cntr-c to cancel the operation and return to a prompt.

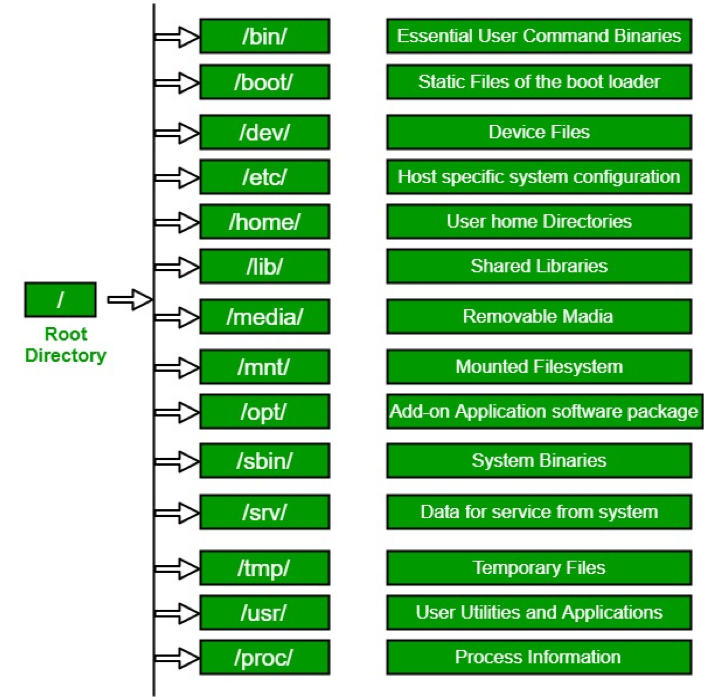

Directory Structure

Absolute path: always starts with ”/”

/share/workshop/msettles/cli

the folder (or file) cli in the folder msettles in the folder workship in the folder share from root.

Relative path: always relative to our current location.

a single dot (.) refers to the current directory

two dots (..) refers to the directory one level up

Usually, /home is where the user accounts reside, ie. user’s ‘home’ directory. For example, for a user that has a username of “msettles”: their home directory is /home/msettles It is the directory that a user is located after starting a new shell or logging into a remote server .

The tilde (~) is a short form of a user’s home directory.

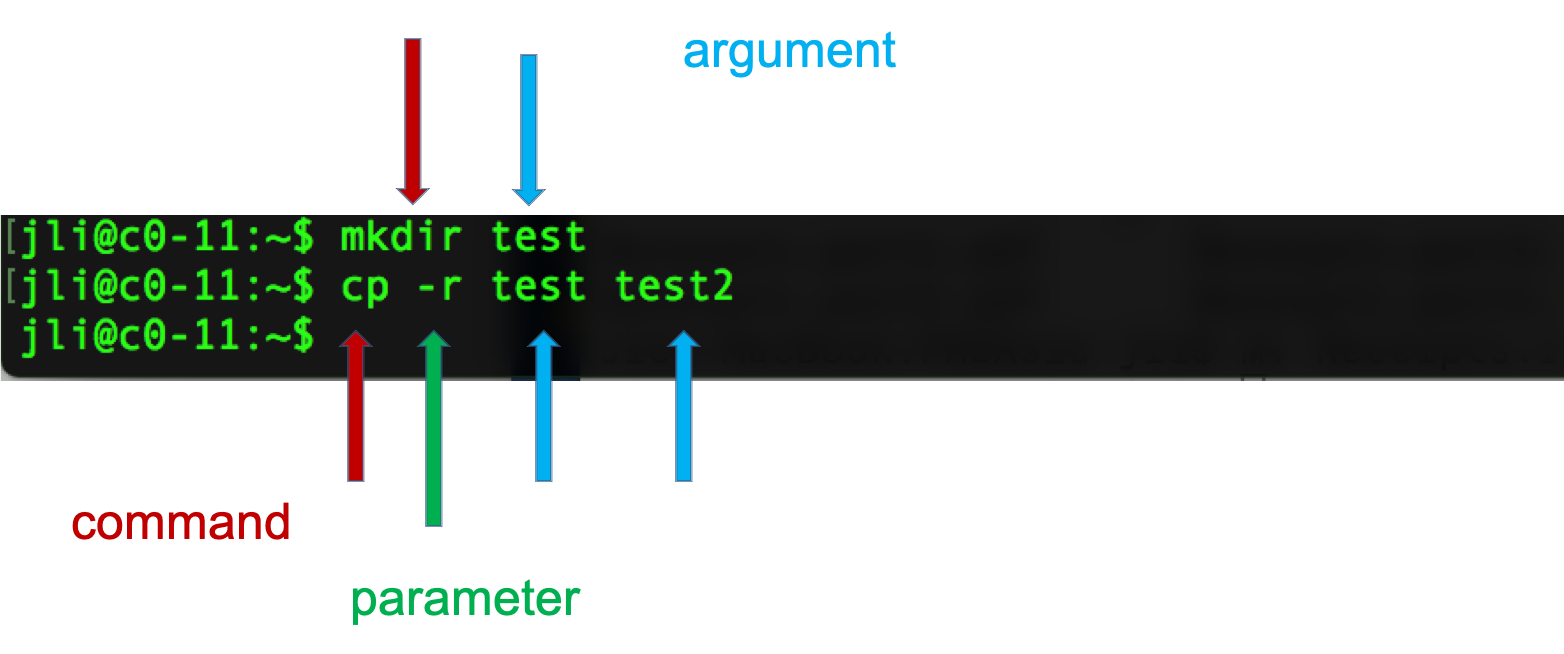

Syntax of a command

- A command plus the required parameters/arguments

- The separator used in issuing a command is space, number of spaces does not matter

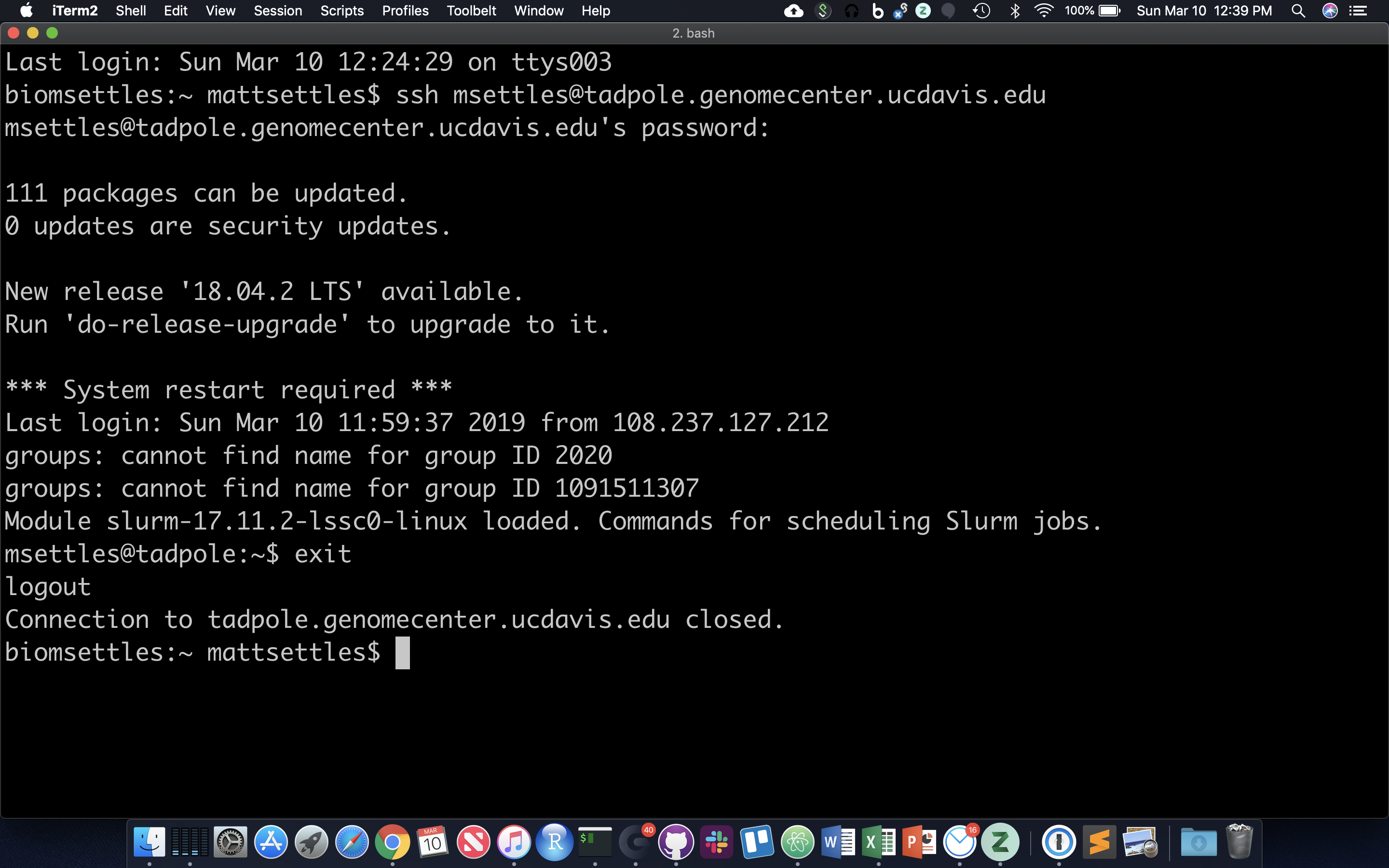

Logging into a remote server

For this we use the application Secure SHell … SSH. Replace ‘username’ with your login name in the following and enter your password when prompted. You will not see your password being typed.

ssh username@tadpole.genomecenter.ucdavis.edu

for example my login is

ssh msettles@tadpole.genomecenter.ucdavis.edu

Once you’re done working on the command line, you can exit. Anything that follows the character ‘#’ is ignored.

exit # kills the current shell!

Go ahead and log back into the server.

After opening, system messages are often displayed, followed by the “prompt”. A prompt is a short text message at the start of the command line and ends with ‘$’ in bash shell, commands are typed after the prompt. The prompt typically follows the form username@server:location$

Command Line Basics

First some basics - how to look at your surroundings.

pwd

present working directory … where am I?

ls .

list files here … you should see nothing since your homes are empty

ls /tmp/

list files somewhere else, like /tmp/

Because one of the first things that’s good to know is how to escape once you’ve started something you don’t want.

sleep 1000 # wait for 1000 seconds!

Use Ctrl-c (shows as ‘^C’ in screen) to exit (kill) a command. In some cases, a different key sequence is required (Ctrl-d).

Options

Each command can act as a basic tool, or you can add ‘options’ or ‘flags’ that modify the default behavior of the tool. These flags come in the form of ‘-v’ … or, when it’s a more descriptive word, two dashes: ‘--verbose’ … that’s a common (but not universal) one that tells a tool that you want it to give you output with more detail. Sometimes, options require specifying amounts or strings, like ‘-o results.txt’ or ‘--output results.txt’ … or ‘-n 4’ or ‘--numCPUs 4’. Let’s try some, and see what the man page for the ‘list files’ command ‘ls’ is like.

ls -R /

Lists directories and files recursively. how do I know which options do what?

man ls

Navigate like in ‘less’ (up,down,pgup,pgdn,g,G,/pattern,n,N,q), look up and try the following, if you don’t say where, it lists files in your current directory

ls -l

ls -a

ls -l -a

ls -la # option 'smushing' ... when no values need specifying

ls -ltrha

And finally adding color:

ls -ltrha --color # single letter (smushed) vs word options (Linux)

OR

ls -ltrhaG # (MacOS)

Quick aside: what if I want to use same options repeatedly? and be lazy? You can create a shortcut to another command using ‘alias’.

alias ll='ls -lah'

ll

Getting Around

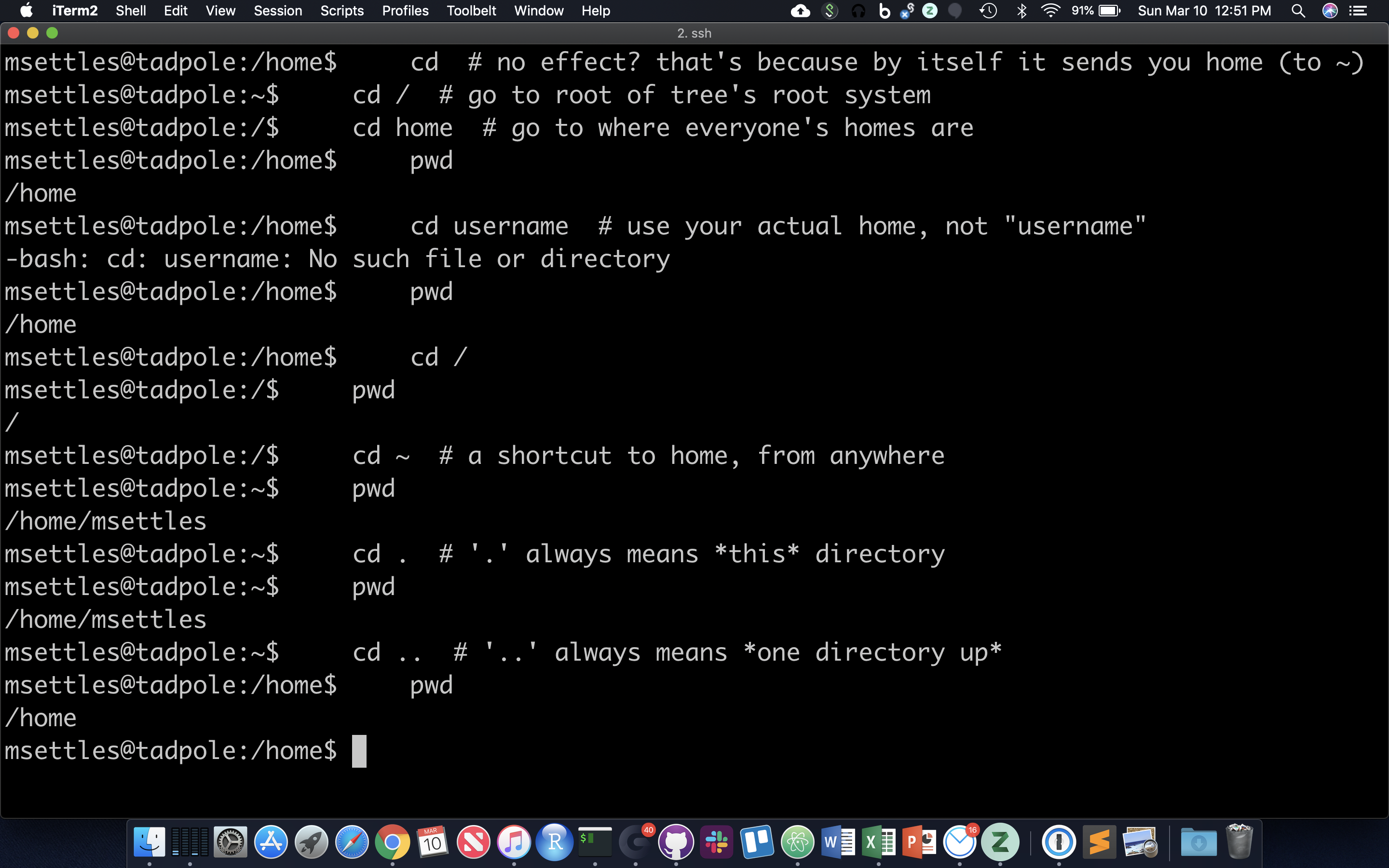

The filesystem you’re working on is like the branching root system of a tree. The top level, right at the root of the tree, is called the ‘root’ directory, specified by ‘/’ … which is the divider for directory addresses, or ‘paths’. We move around using the ‘change directory’ command, ‘cd’. The command pwd return the present working directory.

cd # no effect? that's because by itself it sends you home (to ~)

cd / # go to root of tree's root system

cd home # go to where everyone's homes are

pwd

cd username # use your actual home, not "username"

pwd

cd /

pwd

cd ~ # a shortcut to home, from anywhere

pwd

cd . # '.' always means *this* directory

pwd

cd .. # '..' always means *one directory up*

pwd

You should also notice the location changes in your prompt.

Absolute and Relative Paths

You can think of paths like addresses. You can tell your friend how to go to a particular store from where they are currently (a ‘relative’ path), or from the main Interstate Highway that everyone uses (in this case, the root of the filesystem, ‘/’ … this is an ‘absolute’ path). Both are valid. But absolute paths can’t be confused, because they always start off from the same place. Relative paths, on the other hand, could be totally wrong for your friend if you assume they’re somewhere they’re not. With this in mind, let’s try a few more:

cd ~ # let's start at home

relative (start here, take two steps up, then down through share and workshop)

cd ../../share/workshop/

pwd

absolute (start at root, take steps)

cd /share/workshop/

pwd

Now, because it can be a real pain to type out, or remember these long paths, we need to discuss …

Tab Completion

Using tab-completion is a must on the command line. A single

touch updates the timestamp on a file, here we use it to create three empty files.

mkdir ~/tmp

cd ~/tmp

touch one seven september

ls o

tab with no enter should complete to ‘one’, then enter

ls s

tab with no enter completes up to ‘se’ since that’s in common between seven and september. tab again and no enter, this second tab should cause listing of seven and september. type ‘v’ then tab and no enter now it’s unique to seven, and should complete to seven. enter runs ‘cat seven’ command.

I can’t overstate how useful tab completion is. You should get used to using it constantly. Watch experienced users type and they maniacally hit tab once or twice in between almost every character. You don’t have to go that far, of course, but get used to constantly getting feedback from hitting tab and you will save yourself a huge amount of typing and trying to remember weird directory and filenames.

CHALLENGE

After returning to your home directory (just enter ‘cd’ by itself), verify that the two following commands are equivalent (replacing ‘username’ with your actual username):

cd ../../home/username/

cd ../../../../../../../home/username/

Why are these very different-looking commands equivalent??

Create and Destroy

We already learned one command that will create a file, touch. Lets create a folder in /share/workshop for you to work in and then another directory cli. We will use the environment variable $USER, that is your username.

cd # home again

echo $USER # echo to screen the contents of the variable $USER

cd ~/tmp

echo 'Hello, world!' > first.txt

echo text then redirect (‘>’) to a file.

cat first.txt # 'cat' means 'concatenate'

why ‘concatenate’? try this:

cat first.txt first.txt first.txt > second.txt

cat second.txt

OK, let’s destroy what we just created:

cd ../

rmdir tmp # 'rmdir' meands 'remove directory', but this shouldn't work!

rm tmp/first.txt

rm tmp/second.txt # clear directory first

rmdir tmp # should succeed now

So, ‘mkdir’ and ‘rmdir’ are used to create and destroy (empty) directories. ‘rm’ to remove files. To create a file can be as simple as using ‘echo’ and the ‘>’ (redirection) character to put text into a file. Even simpler is the ‘touch’ command.

mkdir ~/cli

cd ~/cli

touch newFile

ls -ltra # look at the time listed for the file you just created

cat newFile # it's empty!

sleep 60 # go grab some coffee

touch newFile

ls -ltra # same time?

So ‘touch’ creates empty files, or updates the ‘last modified’ time. Note that the options on the ‘ls’ command you used here give you a Long listing, of All files, in Reverse Time order (l, a, r, t).

Piping and Redirection

Pipes (‘|’) allow commands to hand output to other commands, and redirection characters (‘>’ and ‘»’) allow you to put output into files.

echo 'first' > test.txt

cat test.txt

echo 'second' > test.txt

cat test.txt

echo 'third' >> test.txt

cat test.txt

The ‘>’ character redirects output of a command that would normally go to the screen instead into a specified file. ‘>’ replaces, ‘»’ appends.

cuts character one to three, from every line, from file ‘test.txt’

cut -c 1-3 test.txt

same thing, piping output of one command into input of another

cat test.txt | cut -c 1-3

pipes cat to cut to sort (-r means reverse order sort), and then grep searches for pattern (‘s’) matches.

cat test.txt | cut -c 1-3 | sort -r

cat test.txt | cut -c 1-3 | sort -r | grep s

This is a great way to build up a set of operations while inspecting the output of each step in turn. We’ll do more of this in a bit.

History Repeats Itself

Linux remembers everything you’ve done (at least in the current shell session), which allows you to pull steps from your history, potentially modify them, and redo them. This can obviously save a lot of time and typing.

The ‘head’ and ‘tail’ commands view the first 10 (by default) lines of a file and last 10 lines of a file (type ‘man head’ or ‘man tail’ to consult their manuals).

You can also search your history from the command line:

<ctrl-r>fir # should find most recent command containing 'fir' string: echo 'first' > test.txt

<enter> # to run command

<ctrl-c> # get out of recursive search

<ctr-r> # repeat <ctrl-r> to find successively older string matches

CHALLENGE

What’s the first command you executed today? How many times have you used the ‘man’ command today? Whatever that number is, it should be more! Just kidding. Sort of.

CHALLENGE

How would you create a second text file - let’s say ‘test2.txt’ - with the line that says ‘third’ before the line that says ‘second’? Without directly editing the file with a text editor, of course ..

Editing Yourself

Here are some more ways to make editing previous commands, or novel commands that you’re building up, easier:

<up><up> # go to some previous command, just to have something to work on

<ctrl-a> # go to the beginning of the line

<ctrl-e> # go to the end of the line

# now use left and right to move to a single word (surrounded by whitespace: spaces or tabs)

<ctrl-k> # delete from here to end of line

<ctrl-w> # delete from here to beginning of preceeding word

blah blah blah<ctrl-w><ctrl-w> # leaves you with only one 'blah'

Compression and Archives

As file sizes get large, you’ll often see compressed files, or whole compressed folders. Note that any good bioinformatics software should be able to work with compressed file formats.

gzip test.txt

cat test.txt.gz

To uncompress a file

gunzip -c test.txt.gz

The ‘-c’ leaves the original file alone, but dumps expanded output to screen

gunzip test.txt.gz # now the file should change back to uncompressed test.txt

Tape archives, or .tar files, are one way to compress entire folders and all contained folders into one file. When they’re further compressed they’re called ‘tarballs’. We can use wget (web get).

wget ftp://igenome:G3nom3s4u@ussd-ftp.illumina.com/PhiX/Illumina/RTA/PhiX_Illumina_RTA.tar.gz

The .tar.gz and .tgz are commonly used extensions for compressed tar files, when gzip compression is used. The application tar is used to uncompress .tar files

tar -xzvf PhiX_Illumina_RTA.tar.gz

Here -x = extract, -z = use gzip/gunzip, -v = verbose (show each file in archive), -f filename

Note that, unlike Windows, linux does not depend on file extensions to determine file behavior. So you could name a tarball ‘fish.puppy’ and the extract command above should work just fine. The only thing that should be different is that tab-completion doesn’t work within the ‘tar’ command if it doesn’t see the ‘correct’ file extension.

Forced Removal

When you’re on the command line, there’s no ‘Recycle Bin’. Since we’ve expanded a whole directory tree, we need to be able to quickly remove a directory without clearing each subdirectory and using ‘rmdir’.

rm -rf PhiX

Here -r = recursively remove sub-directories, -f means force. We actually want to use those directories, so un-archive them again!

Obviously, be careful with ‘rm -rf’, there is no going back, if you delete something with rm, rmdir its gone!

BASH Wildcard Characters

When we want to specify or operate on sets of files all at once.

ls ?hiX/Illumina

list files in Illumina sub-directory of any directory ending in ‘hiX’

ls PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/*/*.fa

list all .fa files a few directories down. So, ‘?’ fills in for zero or one character, ‘*’ fills in for zero or more characters. find can be used to locate files of a server form.

find . -name "*.f*"

find . -name "*.f?"

how are this different from the previous command?

Quick Note About the Quote(s)

The quote characters “ and ‘ are different. In general, single quotes preserve the literal meaning of all characters between them. On the other hand, double quotes allow the shell to see what’s between them and make substitutions when appropriate. For example:

VRBL=someText

echo '$VRBL'

echo "$VRBL"

However, some commands try to be ‘smarter’ about this behavior, so it’s a little hard to predict what will happen in all cases. It’s safest to experiment first when planning a command that depends on quoting … list filenames first, instead of changing them, etc. Finally, the ‘backtic’ characters ` (same key - unSHIFTED - as the tilde ~) causes the shell to interpret what’s between them as a command, and return the result.

echo `$VRBL` # tries to execute a command with the name *someText*

newVRBL=`echo $VRBL`

echo $newVRBL

Manipulation of a FASTA File

We just found the phiX-174 genome, so let’s copy it to our current directory so we can play with it:

cp ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome.fa phix.fa

Similarly we can also use the move command here, but then ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome.fa will no longer be there:

cp ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome.fa ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome2.fa

ls ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/

mv ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome2.fa phix.fa

ls ./PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/

This functionality of mv is why it is used to rename files.

Note how we copied the ‘genome.fa’ file to a different name: ‘phix.fa’

wc -l phix.fa

count the number of lines in the file using ‘wc’ (word count) and parameter ‘-l’ (lines).

We can use the ‘grep’ command to search for matches to patterns. ‘grep’ comes from ‘globally search for a regular expression and print’.

grep -c '>' phix.fa

Only one FASTA sequence entry, since only one header line (‘>gi|somethingsomething…’)

cat phix.fa

This may not be useful for anything larger than a virus! Let’s look at start codon and 2 following:

grep --color "ATG......" phix.fa

’.’ characters are the single-character wildcards for grep

Use the –color ‘-o’ option to only print the pattern matches, one per line

grep -o "ATG......" phix.fa

Use the ‘cut’ command with ‘-c’ to select characters 4-6, the second codon

grep --color -o "ATG......" phix.fa | cut -c4-6

‘sort’ the second codon sequences (default order is same as ASCII table; see ‘man ascii’)

grep --color -o "ATG......" phix.fa | cut -c4-6 | sort

Combine successive identical sequences, but count them (‘-c’ option)

grep --color -o "ATG......" phix.fa | cut -c4-6 | sort | uniq -c

Finally sort using reverse numeric order (‘-rn’)

grep --color -o "ATG......" phix.fa | cut -c4-6 | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn

… which gives us the most common codons first

This may not be a particularly useful thing to do with a genomic FASTA file, but it illustrates the process by which one can build up a string of operations, using pipes, in order to ask quantitative questions about sequence content. More generally than that, this process allows one to ask questions about files and file contents and the operating system, and verify at each step that the process so far is working as expected. The command line is, in this sense, really a modular workflow management system.

CHALLENGE

Many programs and data archives contain files named something like ‘readme’ or ‘README’ that contains important information for the user. How many of these files are there in the PhiX directory tree? How would you look at their contents?

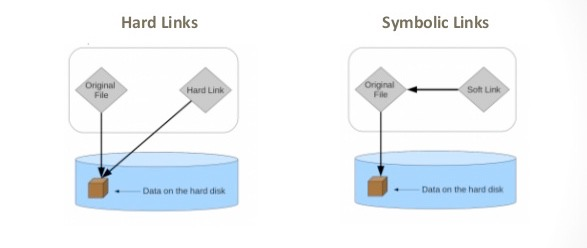

Symbolic Links

Since copying or even moving large files (like sequence data) around your filesystem may be impractical, we can use links to reference ‘distant’ files without duplicating the data in the files. Symbolic links are disposable pointers that refer to other files, but behave like the referenced files in commands.

You should, by default, always use a symbolic (-s) link.

Hard links point to the location of the data on the hard drive while symbolic links point to an secondary location of the data on the hard drive (or the original file itself)

Draw back of hard links is that deleting the original file become much more difficult because all hard links need to be deleted first.

ln -s PhiX/Illumina/RTA/Sequence/WholeGenomeFasta/genome.fa .

ls -ltrhaF # notice the symbolic link pointing at its target

grep -c ">" genome.fa

STDOUT & STDERR

Programs can write to two separate output streams, ‘standard out’ (STDOUT), and ‘standard error’ (STDERR). The former is generally for direct output of a program, while the latter is supposed to be used for reporting problems. I’ve seen some bioinformatics tools use STDERR to report summary statistics about the output, but this is probably bad practice. Default behavior in a lot of cases is to dump both STDOUT and STDERR to the screen, unless you specify otherwise. In order to nail down what goes where, and record it for posterity:

wc -c genome.fa 1> chars.txt 2> any.err

the 1st output, STDOUT, goes to ‘chars.txt’

the 2nd output, STDERR, goes to ‘any.err’

cat chars.txt

Contains the character count of the file genome.fa

cat any.err

Empty since no errors occured.

Saving STDOUT is pretty routine (you want your results, yes?), but remember that explicitly saving STDERR is important on a remote server, since you may not directly see the ‘screen’ when you’re running jobs.

Paste Command

The paste command is useful in creating tables.

echo 'WT1' > b

echo 'WT2' >> b

echo 'control1' >> b

echo 'control2' >> b

cat b

Now we can number our four samples to conveniently refer to them in order

for i in {1..4}; do echo $i >> a; done

cat a

paste a b > c

cat c

Running in the Background

Sometimes it’s useful to continue working on the command line, even after you’ve executed a command that’s going to take a while to finish. Normally this command would occupy the shell, and prevent you from typing in commands and receiving results. But we can ‘put jobs in the background’ so that they don’t occupy your shell directly:

sleep 1000000

Ctrl-Z to pause (stop) the command

bg

To restart the last command in the background

‘^Z’ first suspends the sleep command. Then, ‘bg’ resumes running that command in the background, so that it doesn’t occupy the terminal. The output of the ‘bg’ command tells you that you have one command running in the background. You could start more, suspend them, then resume them in the background, and query what background jobs are running or are suspended, not running:

jobs

We can also start a job in the background in one step, without having to suspend then resume it, using the ‘&’ character at the end of the command:

sleep 5000000 &

If we want to delete these jobs for any reason, we can kill them using the numbering that ‘jobs’ reveals:

jobs

kill %1

jobs

kill %2

jobs

Finally, the ‘nohup’ command (from ‘no hangup’!) makes jobs extra resistant to lost connections or terminal problems. In other words, even jobs running in the background can be terminated if one’s shell dies. ‘nohup’ separates the running job from the shell, so it’ll keep running until it dies or is actively killed by you.

nohup sleep 1000000 &

jobs

output is dumped into the ‘nohup.out’ file unless specifically redirected in your command

kill %1

If you used bg to send a process to the background you can use ‘disown’ to “nohup” the process

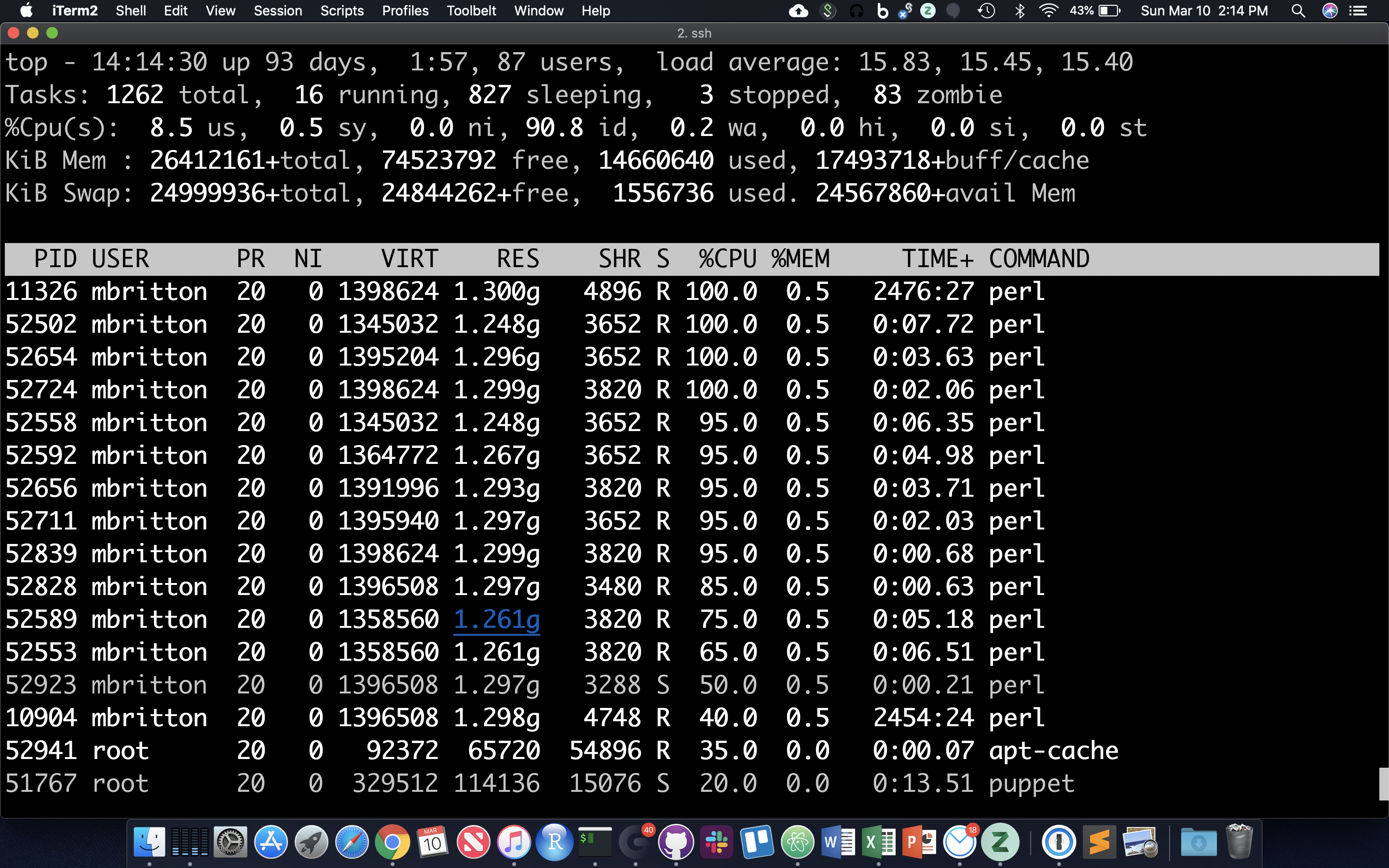

Table of Processes (top)

The ‘top’ command prints a self-updating table of running processes and system stats. Use ‘q’ to exit top, ‘z’ to toggle better color contrast, ‘M’ to sort by memory use, ‘P’ to sort by processor use, and ‘c’ to toggle display of the full commands. Hit ‘1’ to toggle display of all processors, and hit ‘u’ followed by typing in a username in order to only show processes (jobs) owned by that user.

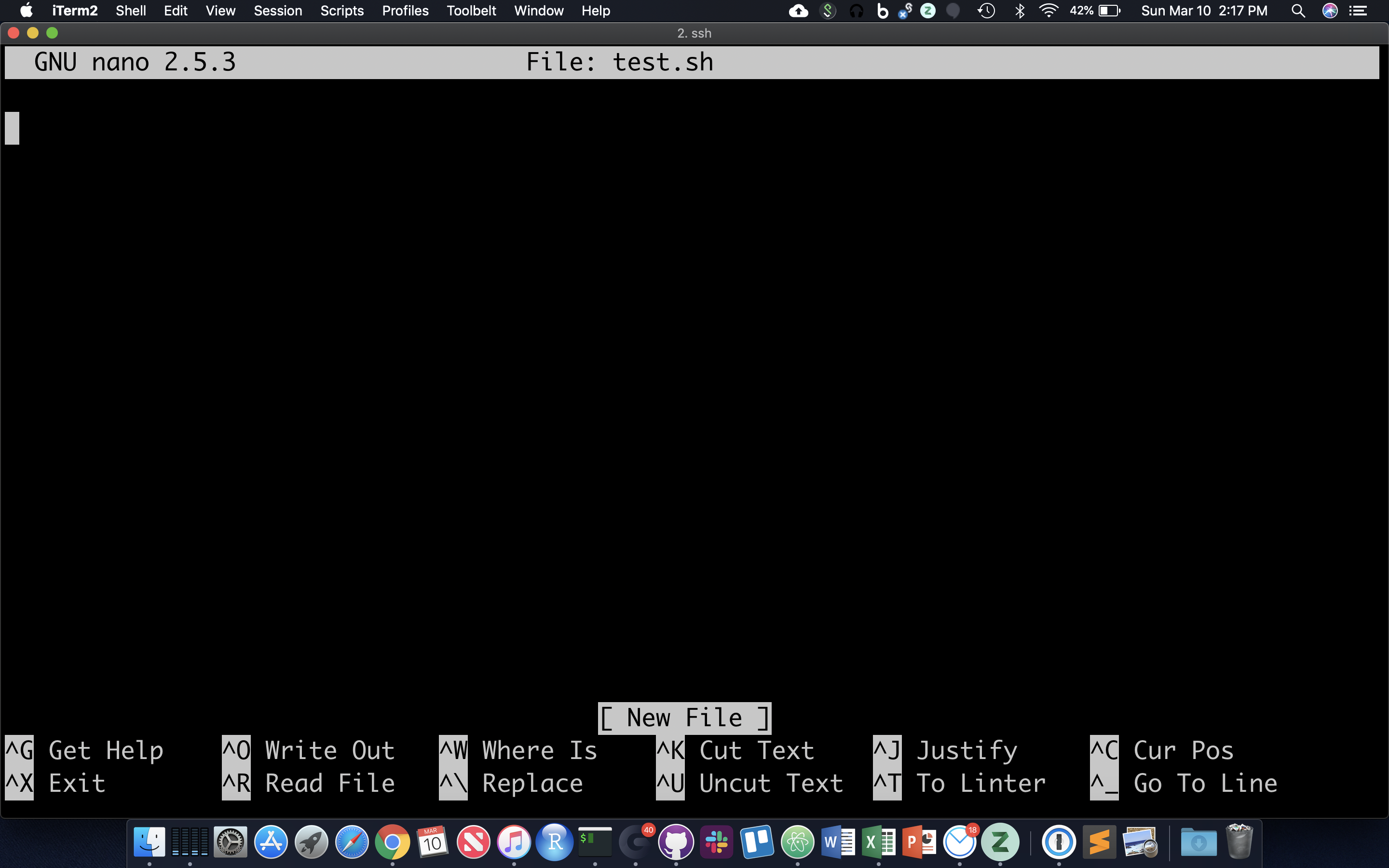

Shell Scripts, File Permissions

Often it’s useful to define a whole string of commands to run on some input, so that (1) you can be sure you’re running the same commands on all data, and (2) so you don’t have to type the same commands in over and over! Let’s use the ‘nano’ text editor program that’s pretty reliably installed on most linux systems.

nano test.sh

nano now occupies the whole screen; see commands at the bottom type/paste in the following … (note that ‘#!’ is an interpreted command to the shell, not a comment)

Cntrl-X top exit first saving the document. Follow the instruction at the bottom of the screen

Note that ‘$1’ means ‘the value of the 1st argument to the shell script’ … in other words, the text that follows the shell script name when we run it (see below).

Though there are ways to run the commands in test.sh right now, it’s generally useful to give yourself (and others) ‘execute’ permissions for test.sh, really making it a shell script. Note the characters in the first (left-most) field of the file listing:

ls -lh test.sh

The first ‘-‘ becomes a ‘d’ if the ‘file’ is actually a directory. The next three characters represent read, write, and execute permissions for the file owner (you), followed by three characters for users in the owner’s group, followed by three characters for all other users. Run the ‘chmod’ command to change permissions for the ‘test.sh’ file, adding execute permissions (‘+x’) for the user (you) and your group (‘ug’):

chmod ug+x test.sh

ls -lh test.sh

The first 10 characters of the output represent the file and permissions. The first character is the file type, the next three sets of three represent the file permissions for the user, group, and everyone respectively.

- r = read

- w = write

- x = execute

OK! So let’s run this script, feeding it the phiX genome. When we put the genome file 1st after the name of the script, this filename becomes variable ‘1’, which the script can access by specifying ‘$1’. We have to provide a relative reference to the script ‘./’ because its not our our “PATH”.

./test.sh genome.fa

The script’s grep command splits out every character in the file on a separate line, then sorts them so it can count the occurrences of every unique character and show the most frequent characters first … a quick and dirty way to get at GC content.