Introduction to the Command Line Interface, part 1

What is the command line?

The command line interface (CLI) is a text-based interface into which the user types commands in order to type commands and perform tasks. Most of the time when using the CLI, your mouse will not work.

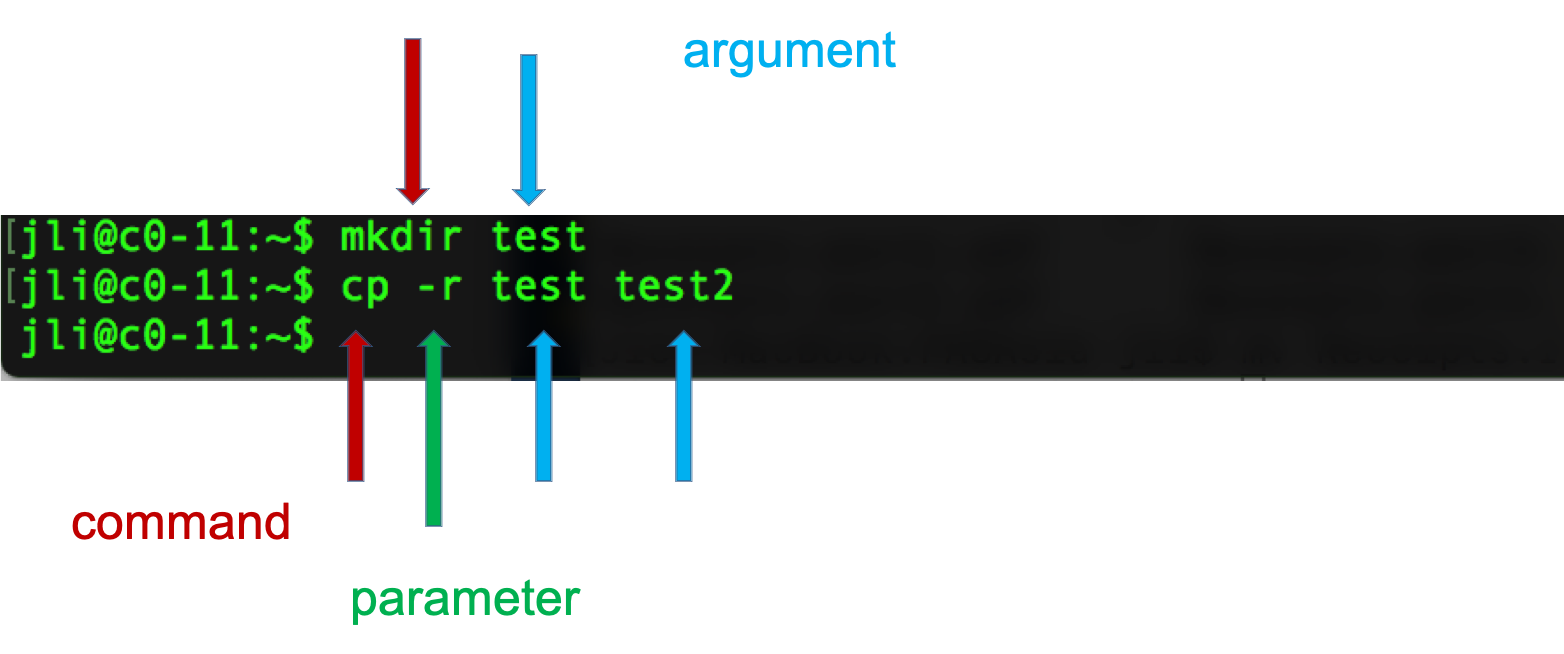

Syntax of a command

A command is made up of components separated by spaces:

- Prompt

- Command (or program)

- Parameters

- Arguments

- The separator used in issuing a command is space, number of spaces does not matter

A greater than sign (>) instead of a prompt means the shell is expecting more input. You can use Cntr-c to cancel the operation and return to a prompt.

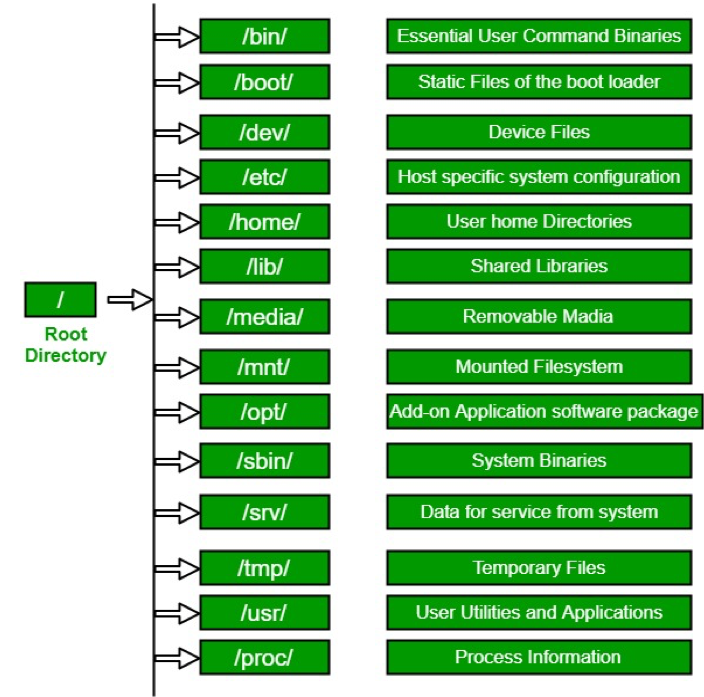

Directory Structure

Absolute path: always starts with ”/”

/share/workshop/prereq_workshop/

the folder (or file) prereq_workshop in the folder workshop in the folder share from root.

Relative path: always relative to our current location.

a single dot (.) refers to the current directory two dots (..) refers to the directory one level up

Usually, /home is where the user accounts reside, ie. user’s ‘home’ directory. For example, for a user that has a username of “hannah”: their home directory is /home/hannah It is the directory that a user is located after starting a new shell or logging into a remote server .

The tilde (~) is a short form of a user’s home directory.

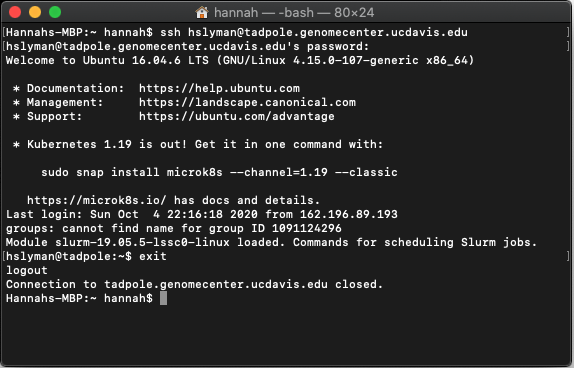

Logging into a remote server

For this we use the application Secure SHell … SSH. Replace ‘username’ with your login name in the following and enter your password when prompted. You will not see your password being typed.

ssh username@tadpole.genomecenter.ucdavis.edu

for example my login is

ssh hslyman@tadpole.genomecenter.ucdavis.edu

Once you’re done working on the command line, you can exit. Anything that follows the character ‘#’ is ignored.

exit # kills the current shell!

Go ahead and log back into the server.

After opening, system messages are often displayed, followed by the “prompt”. A prompt is a short text message at the start of the command line and ends with ‘$’ in bash shell, commands are typed after the prompt. The prompt typically follows the form username@server:location$

Command Line Basics

First some basics - how to look at your surroundings.

pwd

present working directory … where am I?

ls .

list files here … you should see nothing since your homes are empty

ls /tmp/

list files somewhere else, like /tmp/

Because one of the first things that’s good to know is how to escape once you’ve started something you don’t want.

sleep 1000 # wait for 1000 seconds!

Use Ctrl-c (shows as ‘^C’ in screen) to exit (kill) a command. In some cases, a different key sequence is required (Ctrl-d).

Options

Each command can act as a basic tool, or you can add ‘options’ or ‘flags’ that modify the default behavior of the tool. These flags come in the form of ‘-v’ … or, when it’s a more descriptive word, two dashes: ‘--verbose’ … that’s a common (but not universal) one that tells a tool that you want it to give you output with more detail. Sometimes, options require specifying amounts or strings, like ‘-o results.txt’ or ‘--output results.txt’ … or ‘-n 4’ or ‘--numCPUs 4’. Let’s try some, and see what the man page for the ‘list files’ command ‘ls’ is like.

ls -R /

Lists directories and files recursively. How do I know which options do what?

man ls

Within the man pages, navigate using the keyboard (spacebar, b, pgup, pgdn, g, G, /pattern, n, N, q). Look up and try the following parameters for the ls command. Remember, if you don’t provide ls with arguments describing where to run the command, ls lists files in your current directory.

ls -l

ls -a

ls -l -a

ls -la # option 'smushing' ... when no values need specifying

ls -ltrha

And finally adding color:

ls -ltrha --color # single letter (smushed) vs word options (Linux)

OR

ls -ltrhaG # (MacOS)

Quick aside: what if I want to use same options repeatedly? and be lazy? You can create a shortcut to another command using ‘alias’.

alias ll='ls -lah'

ll

Getting Around

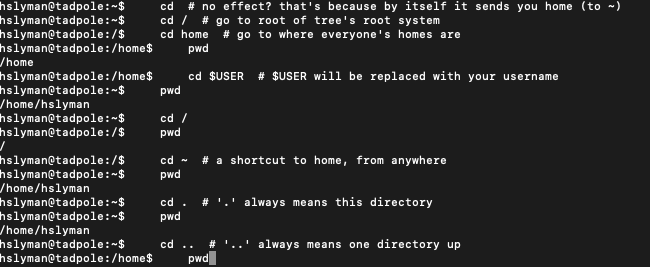

The filesystem you’re working on is like the branching root system of a tree. The top level, right at the root of the tree, is called the ‘root’ directory, specified by ‘/’ … which is the divider for directory addresses, or ‘paths’. We move around using the ‘change directory’ command, ‘cd’. The command pwd return the present working directory.

cd # no effect? that's because by itself it sends you home (to ~)

cd / # go to root of tree's root system

cd home # go to where everyone's homes are

pwd

cd $USER # $USER will be replaced with your username

pwd

cd /

pwd

cd ~ # a shortcut to home, from anywhere

pwd

cd . # '.' always means this directory

pwd

cd .. # '..' always means one directory up

pwd

You should also notice the location changes in your prompt.

Absolute and Relative Paths

You can think of paths like addresses. You can tell your friend how to go to a particular store from where they are currently (a ‘relative’ path), or from the main Interstate Highway that everyone uses (in this case, the root of the filesystem, ‘/’ … this is an ‘absolute’ path). Both are valid. But absolute paths can’t be confused, because they always start off from the same place. Relative paths, on the other hand, could be totally wrong for your friend if you assume they’re somewhere they’re not. With this in mind, let’s try a few more:

cd ~ # let's start at home

relative (start here, take two steps up, then down through share and workshop)

cd ../../share/workshop/prereq_workshop

pwd

absolute (start at root, take steps)

cd /share/workshop/prereq_workshop

pwd

Now, because it can be a real pain to type out, or remember these long paths, we need to discuss …

Tab Completion

Using tab-completion is a must on the command line. A single tab auto-completes file or directory names when there’s only one name that could be completed correctly. If multiple files could satisfy the tab-completion, then nothing will happen after the first tab. In this case, press tab a second time to list all the possible completing names. Note that if you’ve already made a mistake that means that no files will ever be completed correctly from its current state, then tabs will do nothing.

touch updates the timestamp on a file, here we use it to create three empty files.

mkdir -p /share/workshop/prereq_workshop/$USER/tmp

cd /share/workshop/prereq_workshop/$USER/tmp

touch one seven september

ls o

tab with no enter should complete to ‘one’, then enter

ls s

tab with no enter completes up to ‘se’ since that’s in common between seven and september. tab again and no enter, this second tab should cause listing of seven and september. type ‘v’ then tab and no enter now it’s unique to seven, and should complete to seven. enter runs ‘cat seven’ command.

I can’t overstate how useful tab completion is. You should get used to using it constantly. Watch experienced users type and they hit tab once or twice in between almost every character. You don’t have to go that far, of course, but get used to constantly getting feedback from hitting tab and you will save yourself a huge amount of typing and trying to remember weird directory and filenames.

We don’t really need these files, so let’s clean up.

cd ..

rmdir tmp # rmdir means remove directory, but this shouldn't work!

rm tmp/one # clear the directory first

rm tmp/seven

tmp/september

rmdir tmp # should work now that the directory is empty